MIKE: Artist of the Century

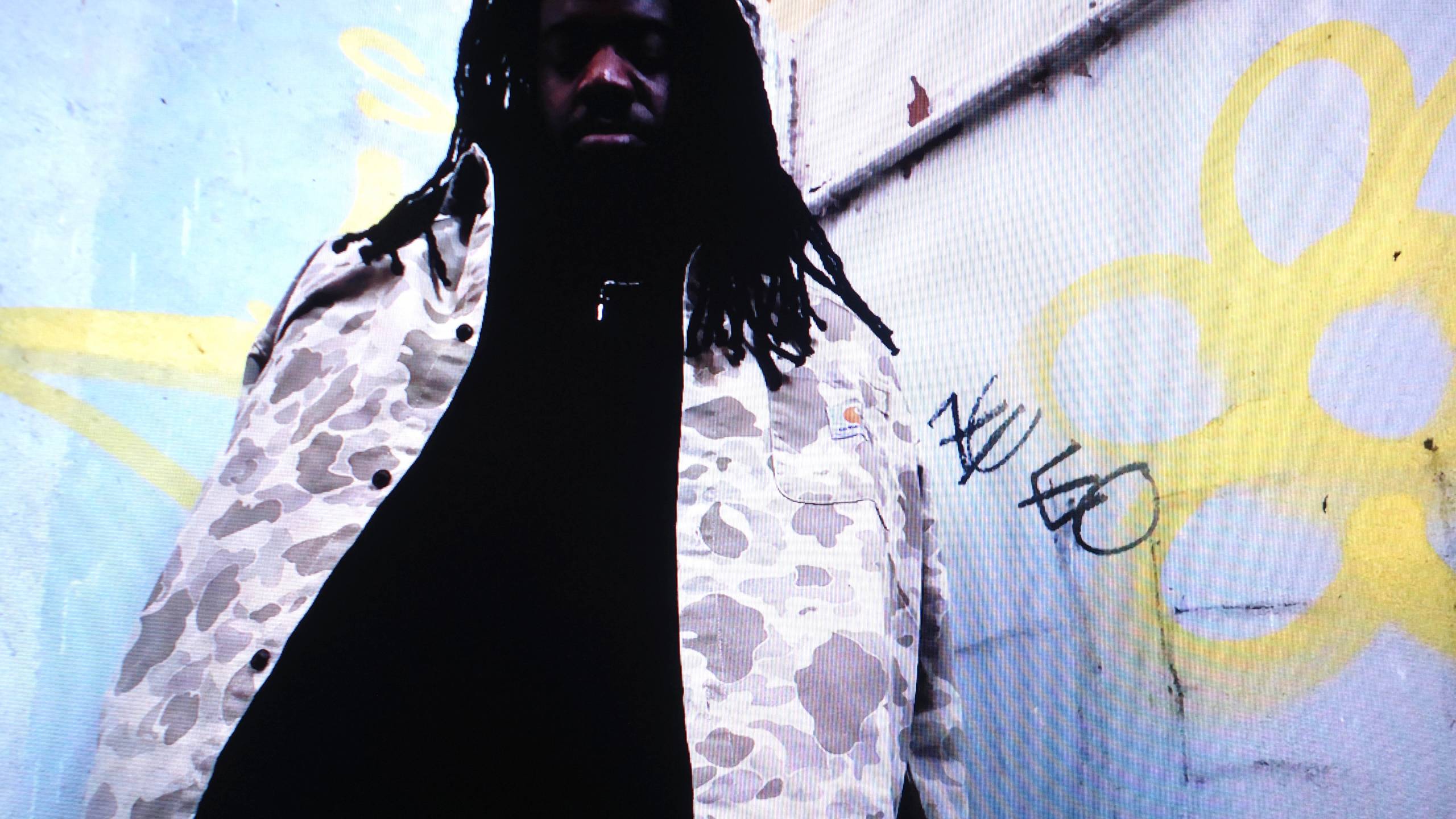

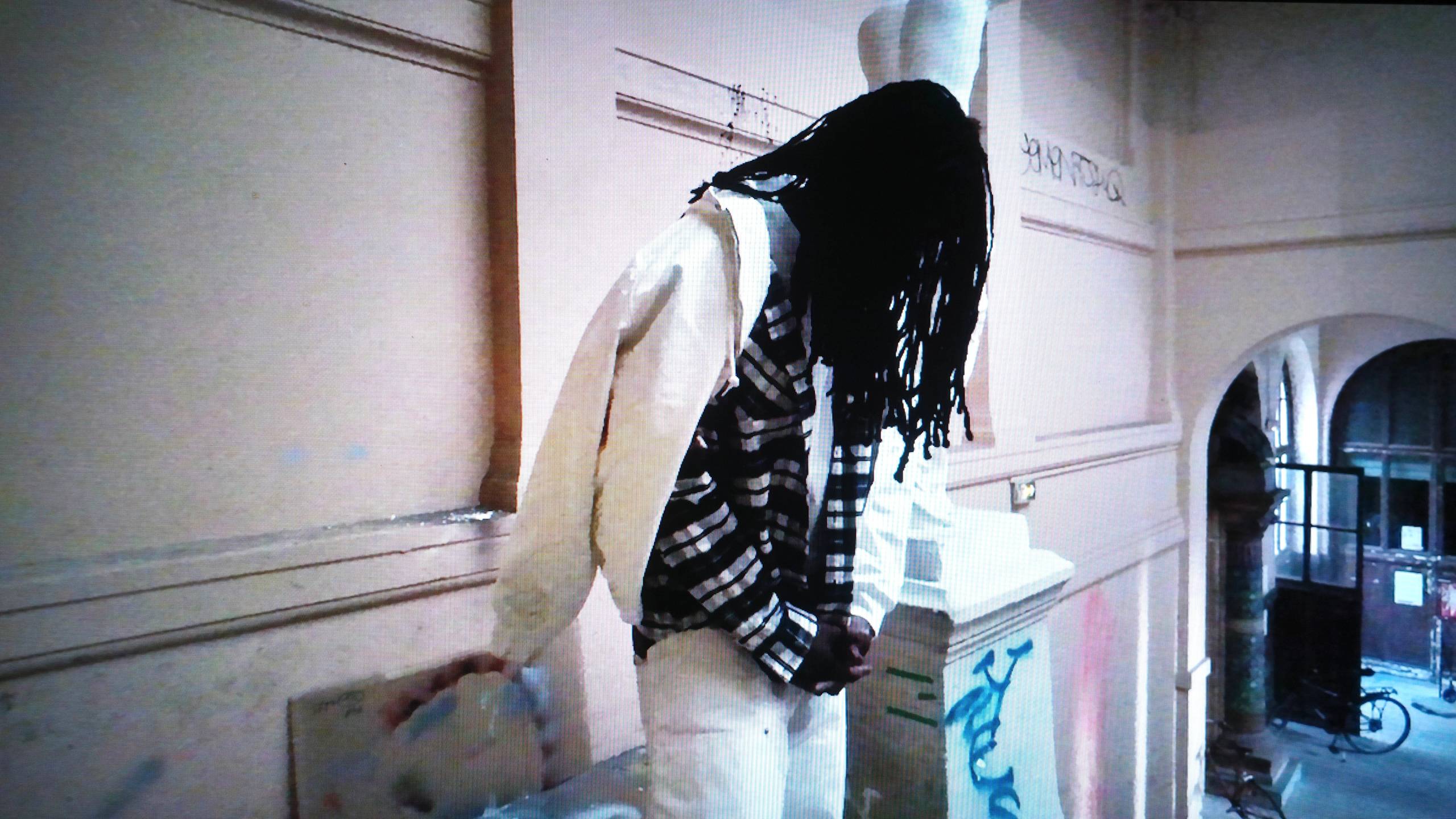

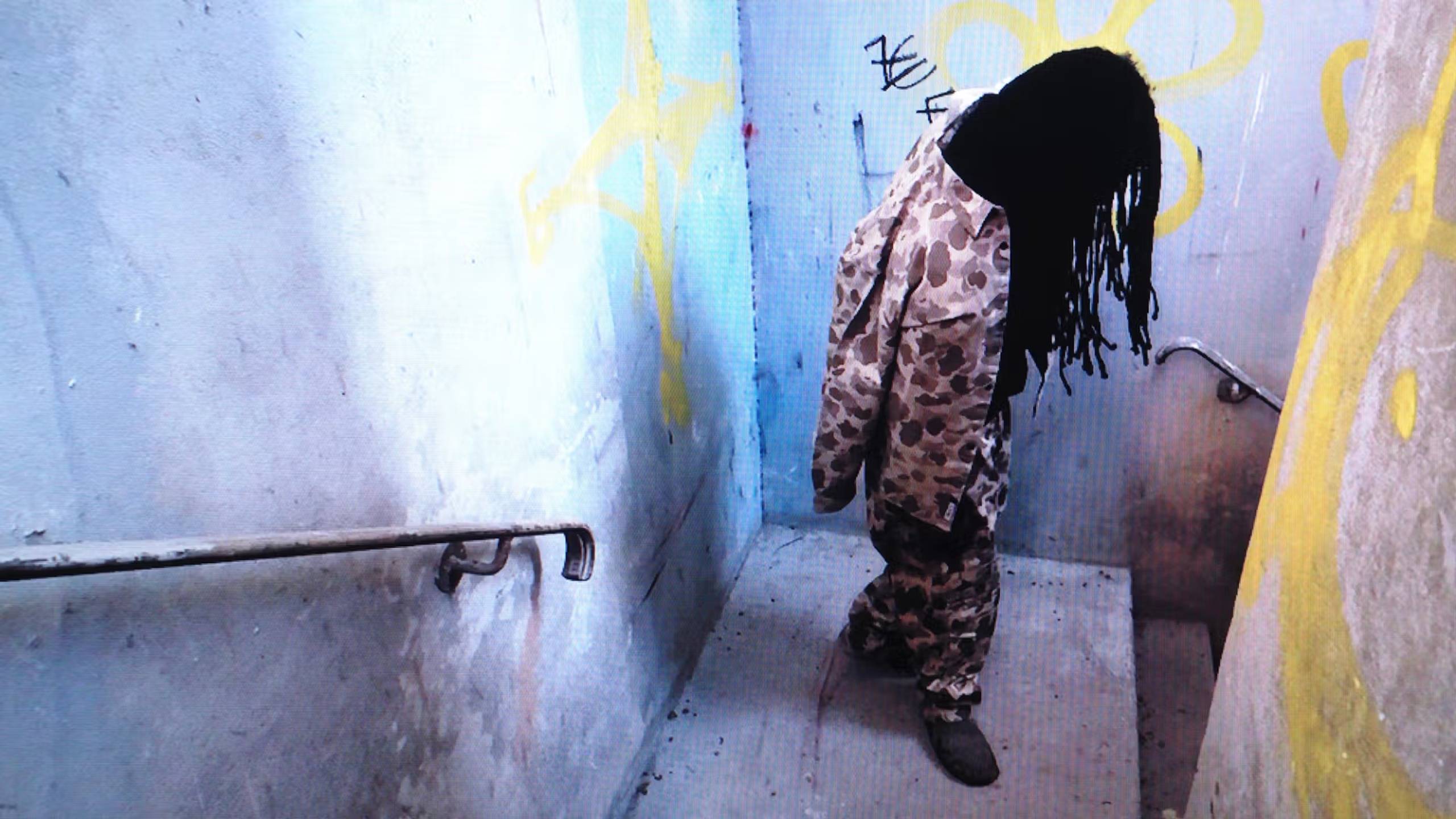

Our first encounter with MIKE, the ascendent 27-year-old rapper, took place in late February at his NYC apartment, as he sat down to discuss his new album, Showbiz!, and his forthcoming European tour. We connected again, five weeks and 30 shows later, in Paris. It was his final stop, before he would return to the US and complete another 40 shows before June. But MIKE is no stranger to the disconcerting feeling that comes with ever-changing locations – his journey to this point has been circuitous, pockmarked by pain, but also perseverance. It might sound obvious to say it, but this route has made him who he is. Here, amidst the crowd at La Maroquinerie, he stands before us.

Take a 2 Train from the Bronx to Penn Station, transfer to the NJ Transit, ride all the way to Trenton, transfer to the SEPTA, then get off at 30th Street, where you will return in a few hours to do it all again, in reverse. This is expensive. This is exhausting. And in the mid-2010s, this is what a teenaged MIKE had to do to visit his father, who was separated from his mother and lived in Philadelphia. A decade on from those days, the wordsmith is a kingpin of East Coast rap, revered in cities that once whizzed by through bus windows. But there was a time, not too long ago, when he felt like “rubbish” in spaces that now exalt him as a hero. Being treated like one is still somewhat new. “There’s, like, private dinners now,” he said, breaking into a belly laugh as we sat together one February afternoon in his Brooklyn apartment. “But there’s deadass been days where I’ve been at Penn Station hungry as fuck.” Earlier that month, he was invited by the New York Knicks to sit courtside at Madison Square Garden, where he was treated with chauffeured meals and VIP service. (Ten years ago? “They probably would have body-slammed my ass!”) A few hours prior to the Knicks game, he had been in a podcast studio with The Kid Mero, wrapping up an extensive press run. And a year or so before that, he had been wading through his memories to craft Showbiz!, a soulful album that reckoned between Mike, the hungry teenager in Penn Station, and MIKE, the star in the VIP section: “It makes me think of how far away you can feel from stuff,” he said, “and how close it actually is.”

One might say the same thing about him. A decade ago, when he began rapping seriously, he joined a litany of jaded New York MCs, bonded by a familiar struggle: growing up in a city that wants to spit you out. (“I hated Penn Station,” he rapped on 2016’s “mines.” “Then I figured that they hated me first.”) This was a generative moment for East Coast hip-hop, foregrounding baby-faced heroes with big shoes to fill. But if Ratking preached brash determinism, and the A$AP Mob preached jiggy escapism, MIKE, along with his sLUms collective, sat somewhere in the middle—humbly disillusioned, candidly unsatisfied. His own music was cold and brooding, as if written at a bus stop in the middle of a winter’s night. He seemed guarded. For a while, he was private on Instagram. You felt far away from him. But then: here was this gravelly voice from the void, saying the realest shit you had ever heard. These were songs about the measly dinners he ate, the phone calls he missed from his parents, the hatred he felt for his own guts, and the depression that wasn’t just a phase. I still have a tape recording of the first time I ever saw MIKE live. We were in a dingy room in Nashville, and he was squinting his eyes shut, sopping with sticky water that could have been sweat, or tears, or both. Whenever I replay my recording, I skip to the two-hour mark, just when he lurches into the wrenching second-half of “weight of the word.” He stops rapping, and there’s this pregnant, stunned silence. No one knows whether to applaud this artist or console this human. I remember Taka, his longtime DJ, looking at him as if to ask whether he was okay.

That was the thing about early MIKE. He carried a certain weight, and when he worked through it on wax, it sounded like he was gurgling on his demons. His was a nomadic upbringing, one that forced him to learn things, to look after himself. “Home” was always changing. Five years in New Jersey, five years in Hackney, London, a stint in Philly with his father, years solo in the Bronx and Brooklyn—all before he turned 18. For the better part of a decade, he was separated from his mother, who lived in the UK, and it filled him with grief. (In 2017, he went on a three-month artist residency in London to be close to her while she battled an illness.) When she passed in 2019, his art became a prayer to her, the sound of someone pleading to a spirit he used to speak to on the phone. “There’s one show happening,” he said of his concerts, between commands to his energetic Boston terrier, Mezcal. “But there’s also another show happening that’s just me and my mom.” This was the spiritual undercurrent of MIKE’s brooding catalog, intimate music weighted as much by loss as self-loathing. But over the years, as his output grew in size and skill, it seemed evident that his spirit was shifting, too. There was a certain point, call it 2021-ish, when a MIKE fan needed to realize—and accept—that their comfort rapper wasn’t morbidly depressed anymore. “Thank my parents ‘cause I age fast, steer me through the flames,” he rapped on “Evil Eye,” the thumping opening track to that year’s Disco!. Gone was the young MIKE who wondered why the world hadn’t been made for him. The grown-up MIKE could make worlds of his own.

This is the headbusting thing about Showbiz!, which presents a world that doesn’t feel all too far from ours. It is violently tangible music—born to rattle speakers, move hips, and squint eyes—about a disarmingly tangible legend, sifting through his detritus and reckoning with who he has become. A longtime listener might perk up at certain Easter-eggs: a flow he favors (compare “Belly 1” to “Iz u Stupid”), a sample he revisits, (compare “The Weight” to “World Market”), a bag he reopens (compare “What U Bouta Do?/A Star was Born” to “plz don’t cut my wings”).

But, more largely, it feels refreshing that the ‘world’ in question isn’t a product of worldbuilding, or constructing some new, marketable mythos. Old Ableton files, old photos, old histories—these things are “time portals,” MIKE said, “to be able to jump back somewhere, come back, and be super grateful.” In our era of underground hip-hop, a lightning-fast revolving door that also basks in excess referentiality, it feels distinctive that his music is unashamedly a relic of itself, unafraid of self-reference and self-revisitation. Showbiz! doesn’t fit into any “era,” or singular, distinctly moodboard-able moment. It lacks a uniform theme or aesthetic. MIKE is stepping into the shoes of his past selves, perfecting their ideas from the present. He is stuck in the midst of it all, and he’s fine. Maybe we can be, too. A few summers ago, Taka told me about a philosophy they share: “[Life]’s gonna go up, it’s gonna go down, it’s gonna go up. But you have to have gratitude in the process of going up — because when you get there, it’s always going to feel good. But when you get back down, you have to understand.” There have been MIKEs that have been down, and other MIKEs that have been up. If Showbiz! showcases anything, it’s the MIKE that understands.

Before Showbiz! came out on streaming services, it premiered exclusively on a website (lostscribe.com) designed by Abe El Makawy and Mikey Saunders, who are also the co-founders of the print shop AINT WET. The site functions as an automatic scroll; the album plays as you sift through disparate ephemera—fit pics, handwritten lyrics, childhood photos, memes, dictums, friends—until the collage, along with the record, ends at the bottom. MIKE’s inspiration was the cover of City Slicker, a 1983 project by the soul singer J. Blackfoot. “It’s him standing in front of the city, in a suit, hella normal. But then there’s the city behind him,” he said. “And there’s hella advertisements, and different shit going on. What it felt like, to me, was: People admire me as the forefront of this shit. But you wouldn’t be able to recognize [Blackfoot] if it weren’t for everything that was going on behind him.” MIKE paused for a little to think, then pivoted to a story from his teeny high school, where solidarity among students was a necessity. (“There’s seven cool kids, ten nerds, ten sports people… and we all fuck with each other.”) When a school-wide benchmark exam was scheduled, the students found the answers online and put them in a calculator. The calculator was discreetly passed around. Come review time, everyone had the exact same scantron. “They called us down to the auditorium, and they were like, ‘Yo, we’re so disappointed,’” MIKE chuckled. “But I’m thinking: look at the community we built amongst each other. People from all different walks of life… y’all should be proud of this.”

Maybe they’d be proud of the community he’s building now. When I visited MIKE in February, he was a few days away from a long flight to Europe, where he would begin a nonstop, months-long gauntlet of tour dates.

Not that this is unusual—MIKE performs so often that he named his album after the business of performing. But he also loves bringing people into his world. And for this particular tour, his world seems so much bigger, so much more flexible, than it once had the capacity to be. 71 dates, 26 openers. Among them: the eclectic UK polymath Pretty V, the Copenhagen singer-guitarist Fine, the Los Angeles experimentalist Salami Rose Joe Louis, the alt-rock provocateur Jespfur, and the New York lyricist Navy Blue. These are each vastly singular worlds in their own right, colliding with one another to forge new, cathartic spectacles. Yet when I think about these collisions, I think specifically of the awkward teenagers out late, the ones who say they “listen to everything” when a classmate asks what they’re into. I think of the fumbling conversations they will have with each other, between sets, underneath the blare of house music, exchanging Spotify profiles. I think of the revelers who will come for MIKE, and leave with 20 Pretty V songs saved to their playlists. And most of all, I think of the fact that ten years ago, MIKE was a hungry teenager in another world, between the Bronx, Penn Station, and Philadelphia—a world that hated him, until he made up his mind to forge a beautiful world of his own.